Gradient boosting and XGBoost – Part 2/2

This is part 2 of ‘Gradient boosting and XGBoost.’ In the first part, we compared random forests and gradient boosting, followed by the installation of XGBoost and training our first XGBoost model. In this chapter, we delve into performance monitoring.

Performance Monitoring

In XGBoost, it’s feasible to monitor the performance of the training process, allowing us to closely observe each stage of the training procedure. To achieve this, after each iteration where a new tree is trained, we can promptly evaluate its performance on our validation data to assess the results. For this purpose, we can establish a watchlist that comprises the datasets we intend to use for evaluation.

watchlist = [(dtrain, 'train'), (dval, 'val')]

By default, XGBoost displays the error rate (logloss), a metric commonly used for parameter tuning. However, given the technical nature of this metric, we’ll opt for another more accessible metric for our analysis.

xgb_params = {

'eta': 0.3,

'max_depth': 6,

'min_child_weight': 1,

'objective': 'binary:logistic',

'nthread': 8,

'seed': 1,

'verbosity': 1,

}

model = xgb.train(xgb_params, dtrain, num_boost_round=200,

evals=watchlist)

# Output:

# [0] train-logloss:0.49703 val-logloss:0.54305

# [1] train-logloss:0.44463 val-logloss:0.51462

# [2] train-logloss:0.40707 val-logloss:0.49896

# [3] train-logloss:0.37760 val-logloss:0.48654

# [4] train-logloss:0.35990 val-logloss:0.48007

# [5] train-logloss:0.33931 val-logloss:0.47563

# [6] train-logloss:0.32586 val-logloss:0.47413

# [7] train-logloss:0.31409 val-logloss:0.47702

# [8] train-logloss:0.29962 val-logloss:0.48205

# [9] train-logloss:0.29216 val-logloss:0.47996

# [10] train-logloss:0.28407 val-logloss:0.47969

# ...

# [195] train-logloss:0.02736 val-logloss:0.67492

# [196] train-logloss:0.02728 val-logloss:0.67518

# [197] train-logloss:0.02693 val-logloss:0.67791

# [198] train-logloss:0.02665 val-logloss:0.67965

# [199] train-logloss:0.02642 val-logloss:0.68022

For our monitoring purposes, we choose to use AUC as the metric, which we’ve previously employed. To do this, we set the eval_metric parameter to auc.

xgb_params = {

'eta': 0.3,

'max_depth': 6,

'min_child_weight': 1,

'objective': 'binary:logistic',

'eval_metric': 'auc',

'nthread': 8,

'seed': 1,

'verbosity': 1,

}

model = xgb.train(xgb_params, dtrain, num_boost_round=200,

evals=watchlist)

# Output:

# [0] train-auc:0.86730 val-auc:0.77938

# [1] train-auc:0.89140 val-auc:0.78964

# [2] train-auc:0.90699 val-auc:0.79010

# [3] train-auc:0.91677 val-auc:0.79967

# [4] train-auc:0.92246 val-auc:0.80443

# [5] train-auc:0.93086 val-auc:0.80858

# [6] train-auc:0.93675 val-auc:0.80981

# [7] train-auc:0.94108 val-auc:0.80872

# [8] train-auc:0.94809 val-auc:0.80456

# [9] train-auc:0.95100 val-auc:0.80653

# [10] train-auc:0.95447 val-auc:0.80851

# ...

# [195] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80708

# [196] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80759

# [197] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80718

# [198] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80719

# [199] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80725

The AUC on the training data reaches perfect accuracy (equal to one), but on the validation data, the performance remains relatively stable at around 80%. This suggests that the model may be overfitting.

To make this output more user-friendly, it would be beneficial to visualize it. Instead of printing output for every epoch, we can use verbose_eval=5 to display results only for every 5th epoch, making the monitoring process more manageable.

xgb_params = {

'eta': 0.3,

'max_depth': 6,

'min_child_weight': 1,

'objective': 'binary:logistic',

'eval_metric': 'auc',

'nthread': 8,

'seed': 1,

'verbosity': 1,

}

model = xgb.train(xgb_params, dtrain, num_boost_round=200,

verbose_eval=5,

evals=watchlist)

# Output:

# [0] train-auc:0.86730 val-auc:0.77938

# [5] train-auc:0.93086 val-auc:0.80858

# [10] train-auc:0.95447 val-auc:0.80851

# [15] train-auc:0.96554 val-auc:0.81334

# [20] train-auc:0.97464 val-auc:0.81729

# [25] train-auc:0.97953 val-auc:0.81686

# [30] train-auc:0.98579 val-auc:0.81543

# [35] train-auc:0.99011 val-auc:0.81206

# [40] train-auc:0.99421 val-auc:0.80922

# [45] train-auc:0.99548 val-auc:0.80842

# [50] train-auc:0.99653 val-auc:0.80918

# [55] train-auc:0.99765 val-auc:0.81114

# [60] train-auc:0.99817 val-auc:0.81172

# [65] train-auc:0.99887 val-auc:0.80798

# [70] train-auc:0.99934 val-auc:0.80870

# [75] train-auc:0.99965 val-auc:0.80555

# [80] train-auc:0.99979 val-auc:0.80549

# [85] train-auc:0.99988 val-auc:0.80374

# [90] train-auc:0.99993 val-auc:0.80409

# [95] train-auc:0.99996 val-auc:0.80548

# [100] train-auc:0.99998 val-auc:0.80509

# [105] train-auc:0.99999 val-auc:0.80629

# [110] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80637

# [115] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80494

# [120] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80574

# [125] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80727

# [130] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80746

# [135] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80753

# [140] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80899

# [145] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80733

# [150] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80841

# [155] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80734

# [160] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80711

# [165] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80707

# [170] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80734

# [175] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80704

# [180] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80723

# [185] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80678

# [190] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80672

# [195] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80708

# [199] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80725

Parsing xgboost’s monitoring output

When you’re interested in visualizing this information on a plot, one of the challenges with XGBoost is that it doesn’t provide an easy way to extract this information since it’s printed to standard output. However, in Jupyter Notebook, there’s a method to capture whatever is printed to standard output and manipulate it. You can use the command %%capture output to achieve this. It captures all the content that the code outputs into a special object, which you can then use to extract the information. It’s worth noting that although something is happening in the code, we won’t see any output because it’s being captured.

%%capture output

xgb_params = {

'eta': 0.3,

'max_depth': 6,

'min_child_weight': 1,

'objective': 'binary:logistic',

'eval_metric': 'auc',

'nthread': 8,

'seed': 1,

'verbosity': 1,

}

model = xgb.train(xgb_params, dtrain, num_boost_round=200,

verbose_eval=5,

evals=watchlist)

s = output.stdout

print(s)

# Output:

# [0] train-auc:0.86730 val-auc:0.77938

# [5] train-auc:0.93086 val-auc:0.80858

# [10] train-auc:0.95447 val-auc:0.80851

# [15] train-auc:0.96554 val-auc:0.81334

# [20] train-auc:0.97464 val-auc:0.81729

# [25] train-auc:0.97953 val-auc:0.81686

# [30] train-auc:0.98579 val-auc:0.81543

# [35] train-auc:0.99011 val-auc:0.81206

# [40] train-auc:0.99421 val-auc:0.80922

# [45] train-auc:0.99548 val-auc:0.80842

# [50] train-auc:0.99653 val-auc:0.80918

# [55] train-auc:0.99765 val-auc:0.81114

# [60] train-auc:0.99817 val-auc:0.81172

# [65] train-auc:0.99887 val-auc:0.80798

# [70] train-auc:0.99934 val-auc:0.80870

# [75] train-auc:0.99965 val-auc:0.80555

# [80] train-auc:0.99979 val-auc:0.80549

# [85] train-auc:0.99988 val-auc:0.80374

# [90] train-auc:0.99993 val-auc:0.80409

# [95] train-auc:0.99996 val-auc:0.80548

# [100] train-auc:0.99998 val-auc:0.80509

# [105] train-auc:0.99999 val-auc:0.80629

# [110] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80637

# [115] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80494

# [120] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80574

# [125] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80727

# [130] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80746

# [135] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80753

# [140] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80899

# [145] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80733

# [150] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80841

# [155] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80734

# [160] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80711

# [165] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80707

# [170] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80734

# [175] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80704

# [180] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80723

# [185] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80678

# [190] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80672

# [195] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80708

# [199] train-auc:1.00000 val-auc:0.80725

Now that we have the captured output in a string, the first step is to split it into individual lines by using the new line operator \n. The result is a string for each line of the output.

s.split('\n')

# Output:

# ['[0]\ttrain-auc:0.86730\tval-auc:0.77938',

# '[5]\ttrain-auc:0.93086\tval-auc:0.80858',

# '[10]\ttrain-auc:0.95447\tval-auc:0.80851',

# '[15]\ttrain-auc:0.96554\tval-auc:0.81334',

# '[20]\ttrain-auc:0.97464\tval-auc:0.81729',

# '[25]\ttrain-auc:0.97953\tval-auc:0.81686',

# '[30]\ttrain-auc:0.98579\tval-auc:0.81543',

# '[35]\ttrain-auc:0.99011\tval-auc:0.81206',

# '[40]\ttrain-auc:0.99421\tval-auc:0.80922',

# '[45]\ttrain-auc:0.99548\tval-auc:0.80842',

# '[50]\ttrain-auc:0.99653\tval-auc:0.80918',

# '[55]\ttrain-auc:0.99765\tval-auc:0.81114',

# '[60]\ttrain-auc:0.99817\tval-auc:0.81172',

# '[65]\ttrain-auc:0.99887\tval-auc:0.80798',

# '[70]\ttrain-auc:0.99934\tval-auc:0.80870',

# '[75]\ttrain-auc:0.99965\tval-auc:0.80555',

# '[80]\ttrain-auc:0.99979\tval-auc:0.80549',

# '[85]\ttrain-auc:0.99988\tval-auc:0.80374',

# '[90]\ttrain-auc:0.99993\tval-auc:0.80409',

# '[95]\ttrain-auc:0.99996\tval-auc:0.80548',

# '[100]\ttrain-auc:0.99998\tval-auc:0.80509',

# '[105]\ttrain-auc:0.99999\tval-auc:0.80629',

# '[110]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80637',

# '[115]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80494',

# '[120]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80574',

# '[125]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80727',

# '[130]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80746',

# '[135]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80753',

# '[140]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80899',

# '[145]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80733',

# '[150]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80841',

# '[155]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80734',

# '[160]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80711',

# '[165]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80707',

# '[170]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80734',

# '[175]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80704',

# '[180]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80723',

# '[185]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80678',

# '[190]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80672',

# '[195]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80708',

# '[199]\ttrain-auc:1.00000\tval-auc:0.80725',

# '']

Each line consists of three components: the number of iterations, the evaluation on the training dataset, and the evaluation on the validation dataset. We can split these components using the tabulator operator \t, resulting in three separate components. To ensure the correct format (integer, float, float), we utilize the strip method and perform the necessary string-to-integer and string-to-float conversions. The following snippet demonstrates these steps.

line = s.split('\n')[0]

line

# Output: '[0]\ttrain-auc:0.86730\tval-auc:0.77938'

line.split('\t')

# Output: ['[0]', 'train-auc:0.86730', 'val-auc:0.77938']

num_iter, train_auc, val_auc = line.split('\t')

num_iter, train_auc, val_auc

# Output: ('[0]', 'train-auc:0.86730', 'val-auc:0.77938')

int(num_iter.strip('[]'))

# Output: 0

float(train_auc.split(':')[1])

# Output: 0.8673

float(val_auc.split(':')[1])

# Output: 0.77938

We can combine all these steps to transform the information (number of iterations, AUC on the training data, and AUC on the validation data) from the output into a dataframe. The following snippet encapsulates all these steps within a single function for ease of use. This allows us to plot the data and perform further analysis.

def parse_xgb_output(output):

results = []

for line in output.stdout.strip().split('\n'):

it_line, train_line, val_line = line.split('\t')

it = int(it_line.strip('[]'))

train = float(train_line.split(':')[1])

val = float(val_line.split(':')[1])

results.append((it, train, val))

columns = ['num_iter', 'train_auc', 'val_auc']

df_results = pd.DataFrame(results, columns=columns)

return df_results

Now, let’s see how the function works in action.

df_score = parse_xgb_output(output)

df_score

| num_iter | train_auc | val_auc | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0.86730 | 0.77938 |

| 1 | 5 | 0.93086 | 0.80858 |

| 2 | 10 | 0.95447 | 0.80851 |

| 3 | 15 | 0.96554 | 0.81334 |

| 4 | 20 | 0.97464 | 0.81729 |

| 5 | 25 | 0.97953 | 0.81686 |

| 6 | 30 | 0.98579 | 0.81543 |

| 7 | 35 | 0.99011 | 0.81206 |

| 8 | 40 | 0.99421 | 0.80922 |

| 9 | 45 | 0.99548 | 0.80842 |

| 10 | 50 | 0.99653 | 0.80918 |

| 11 | 55 | 0.99765 | 0.81114 |

| 12 | 60 | 0.99817 | 0.81172 |

| 13 | 65 | 0.99887 | 0.80798 |

| 14 | 70 | 0.99934 | 0.80870 |

| 15 | 75 | 0.99965 | 0.80555 |

| 16 | 80 | 0.99979 | 0.80549 |

| 17 | 85 | 0.99988 | 0.80374 |

| 18 | 90 | 0.99993 | 0.80409 |

| 19 | 95 | 0.99996 | 0.80548 |

| 20 | 100 | 0.99998 | 0.80509 |

| 21 | 105 | 0.99999 | 0.80629 |

| 22 | 110 | 1.00000 | 0.80637 |

| 23 | 115 | 1.00000 | 0.80494 |

| 24 | 120 | 1.00000 | 0.80574 |

| 25 | 125 | 1.00000 | 0.80727 |

| 26 | 130 | 1.00000 | 0.80746 |

| 27 | 135 | 1.00000 | 0.80753 |

| 28 | 140 | 1.00000 | 0.80899 |

| 29 | 145 | 1.00000 | 0.80733 |

| 30 | 150 | 1.00000 | 0.80841 |

| 31 | 155 | 1.00000 | 0.80734 |

| 32 | 160 | 1.00000 | 0.80711 |

| 33 | 165 | 1.00000 | 0.80707 |

| 34 | 170 | 1.00000 | 0.80734 |

| 35 | 175 | 1.00000 | 0.80704 |

| 36 | 180 | 1.00000 | 0.80723 |

| 37 | 185 | 1.00000 | 0.80678 |

| 38 | 190 | 1.00000 | 0.80672 |

| 39 | 195 | 1.00000 | 0.80708 |

| 40 | 199 | 1.00000 | 0.80725 |

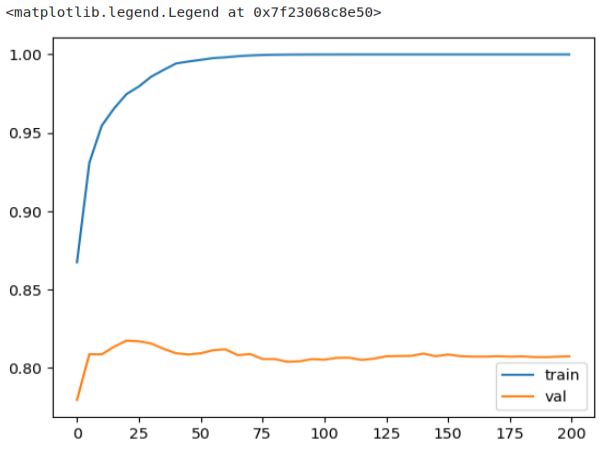

The result of the parse_xgb_output function is a dataframe, enabling us to utilize the plot function for graph visualization.

# x-axis - number of iterations

# y-axis - auc

plt.plot(df_score.num_iter, df_score.train_auc, label='train')

plt.plot(df_score.num_iter, df_score.val_auc, label='val')

plt.legend()

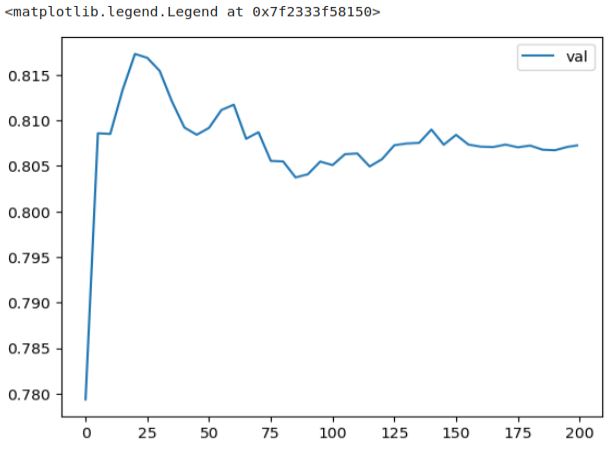

We can observe that the AUC on the training dataset consistently improves. However, the picture is different for the validation dataset. The curve reaches its peak earlier and then starts to decline and stagnate, indicating the onset of overfitting. This decline in performance on the validation dataset is more apparent when plotting only the AUC on validation, while the AUC on the training dataset remains consistently high. The decline in performance is more evident when we exclusively plot the validation graph.

plt.plot(df_score.num_iter, df_score.val_auc, label='val')

plt.legend()