Car price baseline model

This article is about building a baseline model for price prediction of a car. Here we’ll use the implemented code from the last article to build the model. First we start with a simple model while we’re using only numerical columns.

The next code snippet shows how to extract all numerical columns. By the way you can also use it to extract categorical columns.

df_train.dtypes

# Output:

# make object

# model object

# year int64

# engine_fuel_type object

# engine_hp float64

# engine_cylinders float64

# transmission_type object

# driven_wheels object

# number_of_doors float64

# market_category object

# vehicle_size object

# vehicle_style object

# highway_mpg int64

# city_mpg int64

# popularity int64

# dtype: object

df_train.columns

# Output:

# Index(['make', 'model', 'year', 'engine_fuel_type', 'engine_hp',

# 'engine_cylinders', 'transmission_type', 'driven_wheels',

# 'number_of_doors', 'market_category', 'vehicle_size', 'vehicle_style',

# 'highway_mpg', 'city_mpg', 'popularity'],

# dtype='object')

We choose the columns engine_hp, engine_cylinders, highway_mpg, city_mpg, and popularity for our base model.

base = ['engine_hp', 'engine_cylinders', 'highway_mpg', 'city_mpg', 'popularity']

df_train[base].head()

| engine_hp | engine_cylinders | highway_mpg | city_mpg | popularity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 310.0 | 8.0 | 18 | 13 | 1851 |

| 1 | 170.0 | 4.0 | 32 | 24 | 640 |

| 2 | 165.0 | 6.0 | 15 | 13 | 549 |

| 3 | 150.0 | 4.0 | 39 | 28 | 873 |

| 4 | 510.0 | 8.0 | 19 | 13 | 258 |

Value extraction

We need to extract the values to use them in training.

X_train = df_train[base].values

X_train

# Output:

#array([[ 310., 8., 18., 13., 1851.],

# [ 170., 4., 32., 24., 640.],

# [ 165., 6., 15., 13., 549.],

# ...,

# [ 342., 8., 24., 17., 454.],

# [ 170., 4., 28., 23., 2009.],

# [ 160., 6., 19., 14., 586.]])

Missing values

Missing values are generally not good for our model. Therefore, you should always check whether such values are present.

df_train[base].isnull().sum()

# Output:

# engine_hp 42

# engine_cylinders 17

# highway_mpg 0

# city_mpg 0

# popularity 0

# dtype: int64

As you can see there are two columns that have missing values. The easiest thing we can do is fill them with zeros. But notice filling it with 0 makes the model ignore this feature, because:

g(xi) = w0 + xi1w1 + xi2w2

if xi1 = 0 then the last equation simplifies to

g(xi) = w0 + 0 + xi2w2

But 0 is not always the best way to deal with missing values, because that means there is an observation of a car with 0 cylinders or 0 horse powers. And a car without cylinders or 0 horse powers does not make much sense at this point. For the current example this procedure is sufficient for us.

df_train[base].fillna(0).isnull().sum()

# Output:

# engine_hp 0

# engine_cylinders 0

# highway_mpg 0

# city_mpg 0

# popularity 0

# dtype: int64

As you can see in the last snippet, the missing values have disappeared. However, now we need to apply this change in the DataFrame.

X_train = df_train[base].fillna(0).values

X_train

# Output:

# array([[ 310., 8., 18., 13., 1851.],

# [ 170., 4., 32., 24., 640.],

# [ 165., 6., 15., 13., 549.],

# ...,

# [ 342., 8., 24., 17., 454.],

# [ 170., 4., 28., 23., 2009.],

# [ 160., 6., 19., 14., 586.]])

y_train

# Output:

# array([10.40262514, 10.06032035, 7.60140233, ..., 10.92181127,

9.91100919, 8.10892416])

Now we can train our model using the train_linear_regression function that we’ve implemented in the last article. The function return the value for w0 and and array for vector w.

w0, w = train_linear_regression(X_train, y_train)

w0, w

# Output:

# (7.471835414587793,

array([ 9.30959186e-03, -1.19533938e-01, 4.68925224e-02, -1.13441722e-02,

-1.01631104e-05]))

We can use this two variables to apply the model to our training dataset to see how well the model has learned the training data. We do not want the model to simply memorize the data, but to recognize the correlations. Later, we’ll also apply the model to unseen data so that we can eliminate memorization.

y_pred = w0 + X_train.dot(w)

y_pred

# Output:

# array([10.07931663, 9.79812647, 8.84104849, ..., 10.62739988,

9.60798726, 8.97035041])

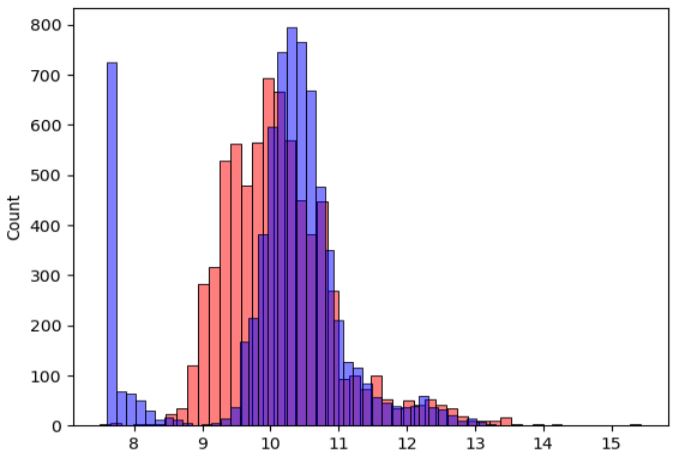

Plotting model performance

Three snippets before, you can see the actual values for y. The last snippet shows the predicted values for y. You could now go through these two lists manually and compare them. A better and also visual possibility is provided by Seaborn. The next snippet shows how to output these two lists accordingly.

# alpha changes the transparency of the bars

# bins specifies the number of bars

sns.histplot(y_pred, color='red', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

sns.histplot(y_train, color='blue', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

You see from this plot that the model is not ideal but it’s better to have an objective way of saying that the model is good or not good. When we start improving the model, we also want to ensure that we really improving it. The next article is about an objective way to evaluate the performance of a regression model.